Poisoned Ground: The Tragedy at Love Canal

Season 36 Episode 4 | 1h 52m 30sVideo has Audio Description

The story of housewives who led a grassroots movement to galvanize the Superfund Bill.

The dramatic and inspiring story of ordinary women who fought against overwhelming odds for the health and safety of their families. In the late 1970s, residents of Love Canal in Niagara Falls, NY, discovered that their homes, schools, and playgrounds were built on top of a former chemical waste dump. Housewives activated to create a grassroots movement that galvanized the landmark Superfund Bill.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate sponsorship for American Experience is provided by Liberty Mutual Insurance and Carlisle Companies. Major funding by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Poisoned Ground: The Tragedy at Love Canal

Season 36 Episode 4 | 1h 52m 30sVideo has Audio Description

The dramatic and inspiring story of ordinary women who fought against overwhelming odds for the health and safety of their families. In the late 1970s, residents of Love Canal in Niagara Falls, NY, discovered that their homes, schools, and playgrounds were built on top of a former chemical waste dump. Housewives activated to create a grassroots movement that galvanized the landmark Superfund Bill.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch American Experience

American Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

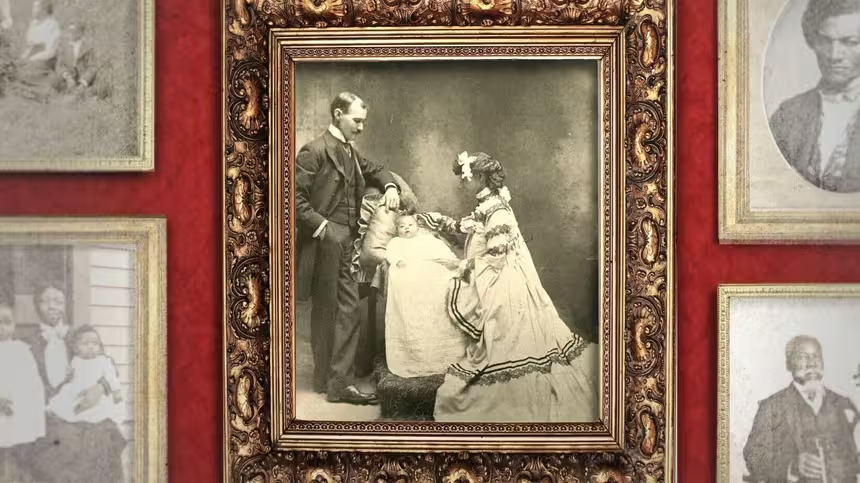

When is a photo an act of resistance?

For families that just decades earlier were torn apart by chattel slavery, being photographed together was proof of their resilience.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

Since pre-colonial times, Americans' relationship to the natural world has shaped politics, policy, commerce, entertainment and culture. In this collection, delve into our complicated history with the environment through American Experience films exploring wide-ranging topics, from our struggles to exert dominion over nature to our attempts to understand and protect it.

Clearing the Air: The War on Smog

Video has Audio Description

The story of L.A.’s noxious smog problem and the creation of the EPA and Clean Air Act. (52m 39s)

Video has Audio Description

Unsung scientist Mária Telkes dedicated her career to harnessing the power of the sun. (52m 22s)

Video has Audio Description

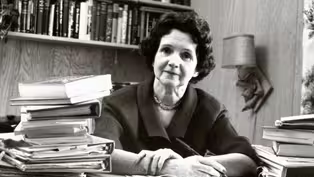

The woman whose groundbreaking books revolutionized our relationship to the natural world. (1h 53m 15s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipARTHUR TRACY: I want to say something.

I'm sure that God is not going to send me to hell, because I found it here on Earth.

(crowd laughing and applauding) I'm 65 years old, almost.

I'm sick and tired of being a yo-yo, pulled this way, pulled that way, pulled the other way!

(crowd cheers and applauds) Now, somebody's gonna say to me, "What do you want, Mr. Tracy, after 35 years in this Love Canal?"

Well, I'll tell you what I want.

Just give me my 28.5 that you appraised my house for.

WOMAN: All right!

TRACY: All I want is my 28.5, and give it to me tonight, and I'll go down that road, and I'll never look back at the Love Canal again!

(crowd cheering and applauding) CROWD (chanting): We want out!

We want out!

We want out!

We want out!

We want out!

We want out!

♪ ♪ BONNIE CASPER (stammers): It was hard to believe.

This could not happen in the United States of America.

REPORTER: For years, the Love Canal Homeowners Association has cited evidence of significant health problems in the neighborhood.

REPORTER 2: Birth defects and miscarriages.

REPORTER 3: Severe migraine headaches.

REPORTER 4: Respiratory disease.

WOMAN: Already eight cases of cancer on a 15-house street.

WOMAN 2: I thought I just had problems with my one daughter, and we just found out in January our other one has rheumatoid arthritis.

We have hearing problems with all the children.

Uh, the baby, he has a deformed foot, so it's just, it's just constantly, still, running to the hospitals and children's hospital... CASPER: People were talking about how they were ill, but nobody exactly knew why they were so ill, or why so many people were so ill. REPORTER: Now, a quarter of a century after it went in, chemical waste is coming out of the ground, and it's... AMY HAY: People had no idea that they were living on top of 22,000 tons of toxic chemicals.

REPORTER: Health experts found more than 80 dangerous chemicals oozing to the surface.

JENNIFER THOMSON: All of a sudden, on a dime, everything blows up.

More people are sick.

There's, you know, black sludge coming into their homes.

REPORTER: The family is afraid to even go in the basement because of high readings of an explosive chemical called toluene.

RICHARD NEWMAN: Love Canal was the first chemical disaster to unfold before Americans' eyes.

LOIS GIBBS (archival): We are dying, literally dying, from benzene.

We're getting cancers from all these other compounds.

Now you're talking about nerve gas-- there's just no way... (in interview): It's much worse than I even imagined.

Certainly much worse than what the government is saying.

Can you tell me when I'm not gonna lose any more children, because one is already dead?

Please tell me those things.

PATTI GRENZY: It really hit it home for us that, at this point, we're on our own.

We have to make this happen.

They're not gonna do it for us.

So, that spurred me to want to do something.

We've got to do something.

I mean, the fight came to us.

We didn't look for it.

Each and every one of you in this room are murderers.

You're a bunch of sick, sadistic people!

PATTI GRENZY: They looked at us as hysterical housewives, and they figured, "Oh, well, they'll give up.

"They'll go back to their knitting, and to their babies, and this will blow over."

But we were stronger than that.

♪ ♪ NEWMAN: This incredible group of women become the faces of environmental reform.

But there was absolutely no road map.

BARBARA QUIMBY: I'm sick of being a guinea pig.

I want out.

Test me later, but my God, get me out now and my kids.

THOMSON: The fear was that it could happen to all of us.

And the thing was, it was happening to other people, in places throughout the country.

REPORTER: The Love Canal is merely the tip of a dangerous and terrifying chemical iceberg.

I am not moving until I get an answer why.

(in interview): I wasn't thinking about building a movement or anything like that.

I was thinking about survival.

(crowd jeering) How do we get out of here?

We need to do something, and I don't care what it takes.

(projector whirring) ♪ ♪ QUIMBY: It was just such a nice neighborhood.

To a child, oh, my goodness, we had fun there.

A lot of times, we would just be more near the school, playing baseball or something, but we always ended up where the, what we called the Black Lagoon.

(camera shutter clicks) PATTI GRENZY: On the surface, it had, like, an oily substance to it, like, a, a green and a blue.

(shutter clicks) And if you dropped something into it, it would bubble up and sink.

So we called it quicksand.

QUIMBY: It was like a wonderland.

We had these rocks that we called pop rocks.

And we used to just slide them across, and they would actually have a flame.

It was like fire.

And, oh, I remember, my mother always yelled about our shoes.

This one time, she had bought me new sneakers.

And I came home, and she said, "What?

It looks like your sneakers are burnt.

"What happened to all the rubber around it?

"You're not getting new sneakers.

What are you doing?"

"I'm just playing at the school."

(laughing): I mean, nobody went and investigated and said, "Why are these shoes burnt?"

♪ ♪ GIBBS: I found the house on 101st Street, the one in the Love Canal neighborhood.

It was starter homes for the most part.

(dog barking in distance) And it was the perfect neighborhood, from my perspective.

It had the Niagara River to the south.

To the north was a creek, and the kids could go and walk along the creek and pick up pollywogs, or... You know, it was just a cute, little, very shallow creek, good for children.

We moved in with Michael, who was one years old by then, a healthy little boy, and, and then we had our little girl.

(camera shutter clicking) I really believed I achieved so much.

I had this house and a husband who was gainfully employed and these beautiful children.

Everything seemed to be fine.

DEBBIE CERRILLO CURRY: Love Canal was government-subsidized.

My husband wasn't making very much money, and they made that a very tasty little deal to move into.

We paid $135 a month to live in a brand-new home, which was really unusual.

I wasn't going to question it.

And so we felt quite lucky that we fell in at the right time.

I lived in Niagara Falls all my life.

And when I married, my husband was from Niagara Falls.

We had two boys.

We saw this beautiful brick house in Love Canal with one acre of land all around it.

And it sat on a creek, and it was just, it was just ideal, and we were thinking, "What a place to raise your children."

JANNIE GRANT-FREENEY: I moved to the development called Griffon Manor.

It was a brand-new housing project.

It's a beautiful place.

Flowers, the grass was green.

There was, like, a little pond that the kids used to play in, and had trees and all of that, and they would swing on the branches and what have you.

CAROL JONES: We had a small yard in the front, and in the back, we would see-- I'm gonna call it water-- but swampland that just looked oily.

(slide shifts) At times, it smelled like burnt rubber or a strong cleanser.

It was just a foul, foul odor.

Often, enough to choke you.

But we didn't pay that any attention.

It was normal to us to smell these smells.

(slide shifts) CURRY: People always knew when they were getting close to our home, because we had this horrendous smell behind our house.

Actually, the whole neighborhood.

REPORTER: The mailman even carries a gas mask on his delivery route.

MAILMAN: It smells like hell.

You got that one house at 510 99th Street.

It's one of the worst smells I ever had around here in a long, long time-- it's terrible.

♪ ♪ CURRY: If you were to drive down Buffalo Avenue, where all the chemical industries were, you would smell that.

My dad worked in the Hooker Chemical.

That was the smell we had from our backyard.

That's why it was real familiar.

It smelled like Dad.

(theme playing) FILM NARRATOR: Today and for the years to come, the world looks for better things for better living through chemistry, the science that has played a major part in the perfection of practically everything we use.

NEWMAN: Niagara Falls in the 1970s is a place that is synonymous with chemicals.

FILM NARRATOR: Chemists make things as far apart as insecticides for the farmer and cosmetics for beautiful women.

NEWMAN: Roughly ten different chemical companies are situated along the banks of the Niagara River.

Before you see the mists of Niagara Falls, you smell all of that chemical production.

It permeates the car, it's in the air, it's thick.

FILM NARRATOR: Substances are shipped out in tank cars and bear names like styrene, vinyl chloride, acrylonitrile.

GIBBS: Chemicals were a part of our life.

You know, when we smelled chemicals, you smelled a good economy.

You knew that you were gonna be able to put food on the table.

You were gonna be able to pay your mortgage.

You're gonna be able to buy a new car someday.

FILM NARRATOR: When modern chemistry and modern industry join hands in serving modern America.

♪ ♪ MARIE RICE: There was a spot in Niagara Falls called Chemical Row, because there were so many chemical manufacturers along there.

♪ ♪ Places like Carborundum and DuPont and Olin.

I know, like, Union Carbide was there.

Goodyear and Goodrich, I think, was also along there.

And then, of course, Hooker-- Hooker Chemical.

♪ ♪ MICHAEL BROWN: Hooker originated in Niagara Falls.

They had started out electrochemicals.

Everything from caustic soda for chlorine to pesticides, herbicides, especially chlorinated hydrocarbons.

Hundreds of chemicals.

Just about any type of chemical that you would need.

Of course, at the same time, these chemicals create toxic waste.

FILM NARRATOR: Hazardous wastes are generated from the production of paints, pesticides, plastics, leather, textiles, medicines.

The challenge is to develop systems to handle the millions of tons of hazardous wastes produced every year.

BROWN: Chemical companies in Niagara Falls and across the United States were dumping in holes.

They were digging, excavating, and, and burying their waste.

That was the way you got rid of it.

FILM NARRATOR: 55-gallon drums are used as containers for solid materials.

They are stacked compactly in the landfill cell, and then cover is applied to keep the rainwater out and keep the waste in.

BROWN: No one back in the '50s knew quite the ramifications, biologically, of many of these chemicals.

GRACE MCCOULF: I used to have garlic and wild onions and strawberries and tomatoes and cucumbers.

(exhales): Beets, carrots.

We used to have everything-- beans.

Italian beans, regular beans.

Just all kinds of stuff, and... CURRY: Nobody could get a garden to grow.

We had one beet grow, and it weighed almost seven pounds.

And you probably would've needed an axe to cut it in half, 'cause it was like, like a small bowling ball.

That was the only beet that grew.

I thought my husband wasn't doing a very good job planting.

(chuckles): I didn't know.

♪ ♪ QUIMBY: We had so many animals die.

It was unexplained.

The fur would just be off of them, or so many of them died cancer.

It seems normal, because it happened to other people's animals, too.

(kids calling in background) GRANT-FREENEY: And then there was something else strange happening.

We would see people were developing what they thought was asthma.

People started to have kidney problems, bladder problems.

Some of the children had behavior problems, a complete change from how they were.

CURRY: So, there were issues.

It did smell.

But the blizzard of '77 was the worst thing could have happened to us.

That blizzard is what brought those barrels up.

♪ ♪ REPORTER: More than 150 inches of snow have fallen so far this year, almost four times the normal average.

What it adds up to is the worst storm of the worst winter in the city's history.

Downtown Buffalo is like a ghost town, nearly all business at a standstill, just like the thousands of cars that have... BROWN: In 1977, I was a reporter for "The Niagara Gazette" covering the city of Niagara Falls.

There had been a very hard winter, and when the snow melted, it was an incredible scene.

(camera shutter clicks) I remember there were drums exposed, they were collapsing, and chemicals came out and started seeping through the ground.

(camera shutter clicks) CURRY: In my backyard, there was a hole in the ground, about the size of a dinner plate.

And it was black goo in it, and it smelled, and it was all foamy around the edges and stuff.

And as the days went on, that hole kept getting bigger and bigger.

And this black goo started to show up in other people's backyards.

MAN: Lived here a good ten years, and they tried to tell me that it's tar, but nobody's been around to check it.

They said, "Well, how about digging it up?"

I've tried to dig it up.

It's just way down deep, and it's all over the backyard.

It's in the side of the field.

It's even in my neighbor's backyard.

And then there started to be something backing up in the basements of our homes in Griffon Manor.

(camera shutter clicks) Black sludge.

And no matter what we did, we couldn't get rid of it.

BROWN: People start telling me things.

And I knew it was anecdotal, uh, information, but I also knew something bad was going on.

NEWMAN: Residents are starting to acknowledge all the weird things that have been going on in the neighborhood for years.

So, the first thing they do is reach out to their local politicians.

Niagara Falls officials really push them off.

That's when they find an angel in John LaFalce, who is the representative for the area of Niagara Falls in Congress.

CASPER: We told several of the residents that we would come out to, to look at the canal.

(talking softly) CASPER: And they took us into their homes.

We went into the basements, and we saw the oozing.

It was like black tar.

I couldn't even truly describe the smell.

Well, it didn't smell like lasagna sauce.

(laughs) It, uh, it smelled like chemicals to me.

Uh, and I wasn't sure what chemicals.

I wasn't sure if it was harmful.

Um, but what you don't know can hurt you.

(camera shutter clicking) CASPER: We could see a couple of the barrels.

And we saw the school.

So there was the playground on the canal.

The residents told us that their kids played in it all the time.

You know, played in the canal, played, that's where they went.

That was their backyard.

(people talking in background) MAN: Okay, give me your last name.

WOMAN: Okay.

LAFALCE (in interview): I wanted to know how it became a dump site for chemicals, and then how that land could have been used for housing, used for a school, used for a playground where kids would be playing on a daily basis.

(talking in background) LAFALCE: I considered the problem a very serious one and was gonna do whatever I thought necessary to deal with it, and that was not the disposition of other officials.

MICHAEL O'LAUGHLIN: I am concerned about the people, all of them.

I can't, as a mayor, though, jeopardize our city.

And a first responsibility I have... LAFALCE: There were some who were very, very worried that this might tarnish the image of the city.

O'LAUGHLIN: And I'm continually being cautioned to be careful not to make blatant statements that could incriminate the city.

♪ ♪ LAFALCE: Niagara Falls, of course, was known for its tourist industry.

And there was an understandable concern about the effect that it would have.

NEWMAN: For centuries, Niagara Falls has had this outsized existence in the American mind.

People have visited it to be overawed by nature, to feel its power.

It's moving.

It's sublime.

But beginning in the 19th and early 20th centuries, a lot of people visited the falls for something else.

They're dead set on developing it for industrial use.

FILM NARRATOR: The mighty waters of Niagara Falls pour some 9,000 cubic feet of water per second over this 165-foot precipice.

NEWMAN: In the 1880s, when hydroelectric power developers arrive in Niagara Falls, they change the falls.

They electrify it, they make it an important part of a new era of hydroelectric power.

FILM NARRATOR: To serve the needs of industry and the welfare of mankind.

NEWMAN: Not just in Western New York, but across the Midwest, Niagara Falls is at the very center of the American industrial dream.

♪ ♪ BROWN: In the 1890s, there was a railroad entrepreneur, William T. Love.

He came up with the idea to build a canal from the upper Niagara River, circumventing the falls, to the lower river.

It was gonna be for transportation and at the same time create power.

NEWMAN: Love wanted to produce something called Model City, merging industrial power with utopian design.

He tells people, "I can create a bigger hydroelectric power station.

I can generate more wealth, more investment in the area."

And people are willing to believe it, because they see Niagara Falls as the next big thing in American industrial life.

William Love is so successful in his investment plan that he actually has enough money to start digging out portions of his canal.

And he's saying to people, "You're walking in the future site of American industrial power right here at Love's Canal."

("Yankee Doodle" playing) BROWN: I mean, he sounded like kind of a showboat.

He would go around with a brass band and circulars and advertisements.

You know, he even had a ditty that was to the sound of "Yankee Doodle."

"Everybody's come to town, those who've left we pity, "for we all have a great old time in Love's new Model City."

(chuckling): Uh, yeah, Love's new Model City.

Uh, he went bankrupt soon afterwards.

♪ ♪ NEWMAN: In many ways, it is a Ponzi scheme.

He promises to pay people in the future, but the future comes on fast.

He can't pay all those debts.

Love's Canal is never finished.

Model City is never completed.

Both of these dreams lie fallow.

And they're sort of a monument to failure.

But there is a groove of earth in the Niagara Falls landscape that's gonna sit there-- no one knows what to do with it.

Enter Hooker Electrochemical Company in Niagara Falls.

KEITH O'BRIEN: In the 1940s, with the war effort in full swing, Hooker Chemical was producing more chemicals than ever before.

And like any manufacturer, it needed someplace to dump its residues and wastes.

NEWMAN: So, Hooker Chemical locates a great area for this just four miles away from its production site, where William Love started building out his artificial river 50 years beforehand.

They think, "This is perfect for burying chemical waste."

BRUCE DAVIS: The canal was further excavated.

And then the drums were stacked into this mini vault.

And then the drums were covered over with four feet of clay.

CHARLES WARREN: And at the time, when there were no laws that governed that dumping, so they just were able to dispose of it in any way they thought was appropriate.

They would back those trucks in.

You know?

MAN: Yeah.

And they would put a drum off here.

Sometimes the lid would come off, sometimes it wouldn't, because they were sealed.

Yeah, now, what happened when that hit the water?

It would come open.

Yeah.

And there would be a flash of flame, like fire going up in the air.

Boom, it would go, you know.

Everybody knew Hooker was a chemical plant.

People certainly knew many of the chemicals that they had produced.

Nobody knew, however, what they had actually dumped as waste material.

And nobody really knew how many drums were buried in Love Canal.

NEWMAN: They filled up the entire area with about 100,000 chemical barrels.

People at Hooker Chemical weren't thinking in terms of long-term chemical risks.

And they thought, when they dumped this stuff, even if it broke out of the chemical drums, the landscape itself would just absorb it like a big sponge.

(kids talking in background) BROWN: In the 1950s, Niagara Falls was an expanding city.

Everything was going great guns, economically.

HAY: Most of the individuals who bought homes worked at Hooker and other chemical companies in Niagara Falls, and so it was seen as this great neighborhood that had good transportation to their jobs at the chemical plants.

NEWMAN: This is a time when people looked at a landscape and didn't worry about what's underneath it.

And Love Canal, the covered-over chemical dump, is actually viewed in the 1950s as a great developmental opportunity.

O'BRIEN: In the spring of 1953, Hooker Chemical sold the land to the Board of Education in Niagara Falls for a dollar.

And they got out of the Love Canal business.

NEWMAN: The Niagara Falls school board signs an agreement with Hooker Chemical, which basically says that there is chemical waste buried underneath the Love Canal site, but it doesn't say exactly what type of chemical waste is in the ground.

This is where they're gonna put the 99th Street School.

They're gonna work with developers to build out a subdivision, which will have new housing stock, playgrounds.

People who are in charge of hazardous waste landfilling were not really concerned about what happens next.

They don't want to know, they don't need to know, because government officials were not pushing them.

For people in Niagara Falls, you don't want to scare off the chemical industry.

Less knowledge is better for business.

LAFALCE: In the summer of '77, I wrote to the head of the Hooker Corporation, saying, "I want to know exactly what you buried.

And I want to know if what you buried could be dangerous."

BROWN: When I first came onto the story, it was an environmental problem.

It was not considered a health threat at that time, at least not that anyone was telling me.

I was shocked when I went door to door and found out that people were actually becoming ill from what was in their homes, the odors that were very obvious at the time.

I contracted asthma.

I lived here three years and discovered I had cancer.

Two children that are legally blind.

My child has rheumatoid arthritis and asthmatic bronchitis, and she is missing part of her second teeth.

BROWN: Everyone had a story, from skin rashes to cancer.

They're talking about birth defects.

They're talking about miscarriages.

My editor held me back from printing a lot of the health effects, because he wanted to hear it from a health official.

When you saw what was going on at Love Canal... (sniffs) (voice breaking): ...it was, uh, very, very difficult... (sniffs, exhales) ...to remain a reporter, because it was like watching an accident in slow motion.

(sniffs) CHILD: Ow, ow, ow, ow!

That's it.

CHILD 2: Ow.

Hold still.

Ouch, ouch, ouch.

Ouch, ouch, ouch.

REPORTER: You could see the fear on faces today as men, women, and children gathered at a neighborhood school on the edge of the former chemical dump for blood tests.

NEWMAN: As state officials learn more, they start extensive testing.

MAN: ...we're looking for evidence of leukemias, anemias, toxic liver conditions.

NEWMAN: They also set up in people's homes.

They went into people's basements.

They monitored leachate, tested what kind of chemicals were maybe seeping into backyards.

(talking in background) BROWN: They had started to conduct air tests.

And for three months, I tried to get the results of those tests.

No one would tell me what they were.

And, finally, I found out that there was benzene in the air there, which was extremely alarming.

That's a known human carcinogen.

REPORTER: The E.P.A.

identified three compounds in quantities 5,000 times higher than levels considered safe.

And three others known to cause cancer in animals measured at 250 times safe exposure levels.

BROWN: And then, things got even worse.

Hooker had another dump that was just across the road from Love Canal.

They also had a dump site next to the water plant, supplies the water for the city of Niagara Falls.

(camera shutter clicking) And their biggest dump was called the Hyde Park Landfill.

And this dump was three, four times the size of Love Canal.

How come we didn't know this?

How could we not know this?

Not only do state officials not know what chemicals are buried here in the Love Canal, they don't even know how many chemical landfills there are in Niagara County.

WARREN: The E.P.A.

said, "We need to get an inventory of toxic sites over the country."

And when we did that, we found many sites of all kinds.

We had them out there, and nobody was doing anything about them.

And, at the time, we didn't think we had the weapons to really deal with those sites.

O'BRIEN: The E.P.A.

was one of the youngest federal agencies, still really finding its footing.

It was founded in 1970 by Richard Nixon.

And it was playing catch-up, especially when it comes to orphaned dumps and chemical landfills.

They were scattered all across America.

WARREN: We actually got a tally, and it was in the thousands.

(helicopter engine running, people talking on radio) NEWMAN: Almost every state has a problem like Love Canal.

And every single one could be a ticking time bomb.

(talking softly) Watch where you're going.

GIBBS: After we lived at Love Canal maybe a year, Michael started getting sick.

So, you know, first it was, like, asthma.

Then it was a urinary disorder.

And, and then, when Michael was in kindergarten, he was spending a lot more time in the school, and that's when he had his first seizure.

We were actually at a fast food restaurant, and I thought he was choking, but he wasn't choking.

And, uh, it scared the dickens out of me.

The pediatrician had no answer.

And so I'm looking at these articles, and I'm reading this stuff about benzene and talulene, and other chemicals-- I didn't even know how to pronounce 'em back then.

And then they were mentioning the 99th Street School.

I'm, like, "Whoa.

Whoa, what is going on here?"

I believe Michael got sick because he was in the school, and also because we played on the playground almost every single day.

(children calling in background) So I put together a petition to close the 99th Street School.

REPORTER: How many chemicals have been identified as being underground here?

MAN: So far, we know of 88 specific chemicals that have been identified.

REPORTER: And of those 88, how many are suspected of causing cancer?

MAN: I think the number's 11.

CURRY: It was really getting kind of frightening.

They were running around in their moon suits.

And they came in with all kinds of machines and stuff so they could do the ambient air in the basement.

They'd say you had benzene and tolulene and trichlorethene and all these enes, and that was Greek to all of us.

And then it wasn't too long after that when Lois showed up at my back door, and I said, "Oh, my God, we went to school together.

We were in Girl Scouts together."

GIBBS: So, we sat in her living room and talked for quite a while.

She talked about her miscarriages, and she talked about all of the other health problems she had.

Debbie was the first one that agreed to go door-knocking with me.

CURRY: I just felt-- sounds silly-- but it was like a calling that I had to do that, and I was hellbent.

PATTI GRENZY: I remember Lois coming down the street with her petition.

And I remember thinking, "Oh, God, what's she selling?"

(chuckles) There were articles in the paper, but I had two young kids and one on the way.

I didn't pay that much attention to the news.

Lois began telling me about birth defects and miscarriages and stillborns and all that.

That's pretty scary, when you're pregnant, to hear that.

We all think, "That's not gonna happen to me.

That happens to the guy, you know, down the street."

Well, we found ourselves being the guy down the street.

It was happening to us.

(helicopter whirring) REPORTER: Today in Albany, the New York State Health Department declared a health emergency in the neighborhood and recommended... O'BRIEN: By August, state officials couldn't sit on this problem anymore.

They make this stunning announcement, encouraging the evacuation of about 200 families living closest to the canal.

REPORTER: ...pregnant women and families with young children... O'BRIEN: But it was just pregnant women or children under the age of two.

WOMAN: My child went to that school for a while.

O'BRIEN: Other people in the neighborhood wondered immediately, of course, about their own health, the health of their children.

LOIS HEISNER: I am really, really afraid.

We have decided we're going to get out, one way or another.

But right now... NEWMAN: People realized they were living not simply on top of a dump that was leaking, they were living in a chemical disaster zone.

And that set off all sorts of terrorizing conversations.

(man talking in background) ♪ ♪ I want to talk first about a number of things... REPORTER: This was the first chance residents had to vent their frustrations into the ears of state officials.

State Health Commissioner Robert Whalen tried to tell the crowd that Albany is doing all that it can to get rid of the poisonous chemicals seeping into their homes.

But the people feel that the wheels of government move too slowly.

And you guys represent us!

You're gonna have problems!

We're gonna do everything... CURRY: The meeting was...

It was doomed to be a screaming match right from the beginning, because we have now been given some information of what we've been exposed to, and how dangerous it really is.

Eight-month-pregnant woman here.

We've lived in that house for two years.

Nobody told us this was happening, man.

Nothing.

She's been there for eight months.

What are you gonna do for my kid?

What are going to do?

Nothing!

MAN (faintly): Where you gonna go?

The damage is done, man, the damage is done.

(audience applauding) NEWMAN: The State Health Department was really most focused on the first two rings of homes around the old canal dumping grounds.

People who weren't in Ring One or Ring Two homes thought that they were trapped in a death zone.

PATTI GRENZY: Ring Three was just outside of that area, which is where we lived.

Our front yard faced 99th Street homes' backyards.

So, we were really, really close.

If this is a ticking health time bomb, why are you only evacuating people who live on 97th and 99th Streets?

REPORTER: Whalen was also criticized for advising only pregnant women and kids under two to evacuate the area.

(shouting): Would you please tell me, do I let my three-year-old stay?

What do you expect of us?

That is my child!

MAN: Ma'am, the... Where is the difference?

What about the seven-... MAN 2: There is no difference!

...and the eight- and the ten-year-olds?

WOMAN: ...the ten-year old kids?!

(applauding) O'BRIEN: Up until that moment, these people believed that government was there to protect 'em.

That government did right by Americans.

These were families who had husbands who had served in Vietnam.

These were mothers who didn't see themselves as part of the feminist movement.

I can't see anything going on in the state of New York that is more important than these people's lives.

(audience cheering and applauding) O'BRIEN: But the community changed that night.

Changed forever.

♪ ♪ REPORTER: As families with pregnant women and small children moved out of their Love Canal homes today and into surplus military housing, New York State officials... LAFALCE: I could very well understand the perspective of the homeowners there.

But I could also understand that this might be a very expensive undertaking.

I'm aware of your problems.

I've been living with them.

I'm aware of your health problems, your housing problems, your school problems.

So I've requested that the Federal Disaster Assistance Administration declare this an emergency and a disaster area.

NEWMAN: Up until that time, the only disasters that had ever received emergency or disaster declarations by the federal government were natural disasters.

So hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes.

But Love Canal is overwhelming all the resources of the local government-- it's even overwhelming the state, and it's rising to the level of a natural disaster.

REPORTER: For the first time, a strictly manmade disaster has been declared a federal emergency, allowing the government to provide assistance to the area.

GIBBS: When Carter says it's an emergency, we're, like, "Yes, now the White House "knows we exist, "we have a problem, and, you know, they're gonna help us."

Money, that's the... That's the good news, money.

O'BRIEN: Governor Hugh Carey comes to Niagara Falls to meet with residents at the 99th Street School.

REPORTER: Hugh Carey talked to residents of the beleaguered Love Canal area.

O'BRIEN: And that night in the school, Carey announces that not only will they be evacuating residents of the neighborhood, but they will buy their homes.

REPORTER: In one of his most popular moves, a promise to pay full market value for the now worthless houses.

(applauding and cheering) BROWN: For the people who were close to the canal, Governor Hugh Carey was a white knight, came in on a horse.

So there was a lot of relief on one hand.

And then you had the other people, who were stuck.

There were about 700 families left behind, and people are watching, just about daily, as more and more is coming out about Love Canal.

REPORTER: It's going to cost more than $9 million to clean up the canal.

And once the work actually begins, it will take three months to complete.

NEWMAN: They want to make sure that the chemicals are contained and they don't leak out to further homes in the subdivision or neighborhood.

REPORTER: The construction plans call for the installation of a clay cap to be laid on top of the canal.

NEWMAN: They're going to seal it up, and it will be covered over with clay.

So they're not taking toxic chemicals out of the ground.

REPORTER: A chain link fence will also be installed here, around the Love Canal area... NEWMAN: But the first thing they do is, they put a fence through the middle of the neighborhood, separating the inner-ring homes, Ring One and Two, from the rest of the neighborhood.

(slide shifts) MICHAEL TOLLI: I remember them putting up the fence.

The first two rows of houses were abandoned.

It was strange.

There's tons of people around, then there's nobody around.

Then, then, you know, now it's a ghost town.

♪ ♪ ERNIE GRENZY: The fence was right down in front of my yard.

And they're saying, "You're okay, this, this... Across the street is not okay."

And that's how we lived for a long time.

(birds cawing) It was devastating.

I mean, you're worried about your kids primarily.

And my wife being pregnant, what's going to happen to the, the baby?

And you're, you're frustrated, because you, you can't do anything about it.

♪ ♪ NEWMAN: Residents at Love Canal, they really thought that the government were going to rescue them, that once they declared that there was a problem at Love Canal, that they would be saved.

And they learned that these officials were dealing with a problem that was as new to them as it was to the residents.

O'BRIEN: They realized that in order to escape from their own homes, in order to even understand the scope of the problem, they need to organize.

♪ ♪ GIBBS: Our first Love Canal Homeowners office was at the 99th Street School.

It was a classroom.

And because I had knocked on everybody's door, they recognized my face.

And so I was voted in as president.

I was terrified of being a leader.

I'm a shy, quiet person, and all of a sudden, having hundreds of people counting on me, and they are angry.

And, and frustrated and terrified, and so it isn't just being a leader, it's being a leader in a crisis.

♪ ♪ RICE: Lois was very nervous, and I always will remember it.

She had her notes kind of scribbled on a small piece of paper, and she was standing in front of the microphones and her hands literally shook, she was so nervous.

But what was so interesting for reporters, we saw her go from that to being unbelievable in front of the cameras.

...come a long way.

We've gotten Ring One evacuated, we've gotten Ring Two evacuated.

We now have an emergency.

They're talking about purchasing our homes in Washington.

The decision is not made.

There's only one thing that's going to make the decision, and that's public opinion.

(audience members exclaiming) So none of you should be... GIBBS (in interview): Our main goal was, anybody who wanted to leave could leave, with their homes being purchased at fair market value.

I wanted out, just like all my neighbors.

Wanted out-- I wanted to be gone.

I wanted somebody to buy my house.

'Cause that's all the assets I had in the world.

Um, and, and I wanted to move, and I wanted to have that happy life I had before, when I would walk my son to school, when I would pack my husband some lunch, and when I would cook a green cake for St. Patrick's Day.

I wanted it all back.

REPORTER: As president of the Love Canal Homeowners Association, Gibbs has gone from quiet housewife to neighborhood advocate to an outspoken spokesperson on the topic of hazardous waste disposal.

Now the Homeowners Association works out of this house, one of the homes abandoned by Love Canal evacuees.

(phones ringing) I mean, we definitely need a doctor tonight.

POZNIAK: ...at John's.

John's.

Now, she told you about the 6:00 bit?

Yeah, why don't... Because they have to be certified... Why don't you talk to Mike...

Okay, why don't you answer that phone?

(chuckles) Love Canal.

Lois.

QUIMBY: I went to the office every single day and opened up.

There was a core group, and we were there every day.

The phone never stopped ringing.

People would come in.

Lois called us all by our last name.

It was like we were in the service.

You know?

In the Army or something.

MCCOULF: My kids were little, so they were in the office with me.

I did some fundraising, sent letters to all kinds of businesses trying to raise money so that we could do things, you know, give meetings, print up flyers.

(people talking in background) CURRY: I was eventually voted in as the vice president, and Lois always used to kid me I was the vice president of the art department, because most of the signs you saw in that neighborhood were built by me.

(chuckles) At that time, I had already moved, so when I could find childcare, I would come back to the office and work with the girls.

I just didn't have the heart to leave them when I had the opportunity to move away from all of the danger.

My heart wouldn't allow it.

My gut told me, "You have to stay there and help."

PATTI GRENZY: When you look back at that time, the men were the ones that got things done.

Men didn't look at women as being smart, as being determined, or stepping outside the circle of their family.

At the office, there were some men that were retired.

Then there were men that worked shift work, so they could be there, as well, but for the most part, it was the women.

It was the moms that did the groundwork.

Okay, tell her that we're going to set up a clinic tonight, probably at Jan's hotel, uh, in room 416.

I just don't know the time yet.

That should be 12:00-- and why does the state want to make things easier for themselves instead of us, huh?

O'BRIEN: Almost everyone fighting to escape was a woman, and almost every person in power was a man.

And so it turned into this real gender battle.

Mrs. Kenny lost a child, I lost a baby before it was even born, my next-door neighbor had a stillborn.

Her son is sick, her son is sick-- how many more kids have to be sick?

How many more kids have to die?

We're not gonna let it happen.

HAY: Activism connected to motherhood has a long, long history in America.

And it is often something that will mobilize, uh, apolitical women.

(slide shifts) It starts with a sincere desire to protect their children.

(slide shifts) But then, once they realize how powerful that is, and how, how effectively it plays in the media, they realize they have a winning strategy.

REPORTER: ...the leader of the group, Lois Gibbs.

A media star: attractive, articulate, and persistent.

O'BRIEN: The press absolutely loved these women.

They gravitated to tell the story of Lois Gibbs.

Lois Gibbs leads the fight for the people still living in the Love Canal area.

Lois Gibbs continues to have doors slammed in her face.

Homeowners president Lois Gibbs has fought for relocation for over 700 Love Canal families.

She's with us tonight.

Mrs. Gibbs, 700 families... (in interview): Instinctively, I knew history was being made here.

And I just felt I had a ringside seat to history and I didn't have to buy a ticket.

The Education Board bought from Hooker, for the price of a dollar, all this land.

QUIMBY: Lois said, "We have to stay in the news."

She kept saying, "We have to keep this front page.

We can't let them forget about us."

GIBBS (archival): We have to keep the pressure on President Carter.

And in order to do that, we're going to have to send telegrams, scream and holler, and be heard.

(applauding and cheering) NEWMAN: Folks covering the Love Canal saga as a media event often-- too often-- focused in on Lois Gibbs and the struggle of the homeowners.

(talking in background) NEWMAN: But there are other people in the neighborhood, people who don't own property in Love Canal, who had many of the same fears, many of the same concerns as the homeowners.

O'BRIEN: Just on the downtown side of the canal was one of the newest public housing developments in the city of Niagara Falls.

It was called Griffon Manor, and it was home to about 250 families.

(children calling) JONES: Griffon Manor, it was just a close-knit community.

Most of the families there were related to each other.

Even before Love Canal was on the news, my mother was talking about it.

I remember she said, "There's more going on here than meets the eye-- we've got to do something."

Our table was completely covered.

My mother had notes everywhere.

There was, uh, research material, newspaper clippings.

There was data from surveys that she had taken from people with health issues, and she found that a lot of the people who lived in Griffin Manor had illnesses that were concerning.

From my memory, my mother should have been on the news every day, because she was always out there talking to reporters, answering questions, offering information, just as Lois Gibbs was.

But there were many nights when we would watch the news, and there would be no clips of anything that she had discussed.

And she'd just sit there at the table, and then she'd just put her head down and she'd just cry.

Love Canal was not Griffon Manor.

They were two different places.

It was like being in two different cities.

MAN: How many families are there amongst the renters in a similar situation?

I would say at least half of the population in that area are severely ill. MAN: Like, I've been living out here since I was about four years old.

I have a, a seizure disorder.

GRANT-FREENEY (in interview): Renters were not getting their health addressed as the homeowners were.

Some of the healthcare professionals, they were saying that because of us not taking care of our children properly, that's the reason why they were sick.

And my doctor, she still don't want to say that, uh, this the, is the cause, or, you know, related to it.

You know?

NEWMAN: Renters feel marginalized on a number of levels.

So Griffon Manor residents form their own activist organization.

WOMAN: Okay, to the people that live in the Niagara Falls Housing Authority, there will be a meeting specifically for us, because this is what happens to us.

We get jumbled into people that own homes... WOMAN: Why don't you buy one?

WOMAN 2: Why don't you buy one?

(audience clamoring) GRANT-FREENEY: We had many meetings with homeowners.

They were mean people.

What they wanted us to do was to stop complaining.

They needed to be taken care of, and then when they got taken care of, then address the renters.

Governor Carey was in Buffalo yesterday, and he especially pointed out to me that, don't forget the people on the outside of the present perimeters, and especially Griffon Manor.

(crowd clamoring) And he, and he...

He, and, so we're very, very aware of it and we're going to be watching it.

I promised, uh, Mrs. Gibbs she could be next.

(audience applauding) JONES: My mom and Lois Gibbs talked about what was going on in Griffon Manor.

There's nothing that makes me believe that Lois wanted anyone to be forgotten about.

But they had different roles to play.

Lois's role was to take care of the people who lived outside of Griffon Manor, and my mother's role was to take care of the people inside.

And it became somewhat of a competition to get what you could for the people that you represented.

♪ ♪ O'BRIEN: Homeowners believed that people living in Griffon Manor could just move.

They were renting.

They weren't invested into their homes with their life savings.

(children calling in background) HAY: But Griffon Manor was some of the best public housing in Niagara Falls.

They had units with three or four bedrooms, which meant that if you had a large family, you could actually live like a family.

There was no comparable public housing anywhere else in Niagara Falls.

GRANT-FREENEY: We did have large families, so of course you would have to rent a house or a large apartment, and it just wasn't affordable for people.

So it was devastating, it really was.

It's like you're in a fire, but you can't get out.

Sometimes, you know, it make you want to cry now, because... (breathes deeply) They had no way out.

No way out.

REPORTER: Finally, late this afternoon, the green light.

Workers wearing air packs and disposable uniforms stood by as the first shovel of dirt was removed from the Love Canal.

Slowly, the odor that the residents here had been living with for years started to permeate the air.

♪ ♪ MAN: As you all know, two of the contaminants that have been found in the canal are benzene and chloroform and carbon tetrachloride.

I'm happy to say, however, that based on what we have seen and evaluated, there is no evidence of benzene toxicity.

STEPHEN LESTER: The state was constantly repeating and trying to reassure the residents and the public that they had things under control, and that, you know, there's no cause for alarm.

MAN: We are coming across some abnormalities in the liver function studies that were performed.

This is to be expected in any population.

As you know, there are a variety of things that can cause liver disease besides toxic chemicals.

LESTER: They would explain that something like a benzene, you would know that it affects the blood, it affects the central nervous system, causes liver damage.

But because you're exposed to only seven parts per million, which is in your house here, that doesn't mean you'll get those.

It means you're at a risk of that.

That, of course, doesn't mean anything to people.

MAN: There are upwards of 200 different chemicals that have been identified.

REPORTER: Here's what the residents did learn.

Tests do show that some children in the area have liver abnormalities.

They don't know whether toxic chemicals are responsible.

But these residents were not satisfied with the answers, and the questions poured out from the angry crowd.

I have an eight-and-a-half- year-old asthmatic.

I have been told by my doctors to get her out of this area.

Do I have to stay in that house until there is worse?

NEWMAN: The folks in the New York State Health Department had their work cut out for them.

Scientists work in labs-- they have protocols.

Those protocols are objective and disinterested.

And any time you talk about anger, feelings, emotions, subjectivity-- the things that Love Canal residents are talking about-- you compromise the process.

And the people are scared.

I worked for Stauffer Chemical for 23 years.

I've seen men die, from fumes.

(audience murmuring) NEWMAN: So when health officials show up on the ground and they start talking to residents, the first thing they realize is, they don't even know how to talk to them.

MAN: They did not say one thing!

They went around in circles all night long.

All night!

This gentleman right here couldn't even answer a question!

(audience cheers and applauds) HAY: Many of the residents did not have degrees beyond high school.

And so there was embedded class and gender tensions that are really exposed.

GIBBS (archival): We asked the state to have the state scientists down here who could answer the residents' questions.

They didn't do it.

PATTI GRENZY: We were more or less self-educating ourselves with the help of some other people.

The more you learned, the more frightening it was, the more determined that we were to succeed at this.

♪ ♪ LESTER: I was just overwhelmed with how hard they worked to learn, and Lois at one point asked me for my toxicology text, from when I was in school, and I gave it to her.

So they were devouring this stuff, and they very quickly became very versed.

And they were highly motivated, because they weren't getting answers from the Health Department, and so where could they turn to get answers?

BEVERLY PAIGEN: In other fields of science, we sometimes talk about gaps in our knowledge.

Here, it's almost, our knowledge is a little gap in our ignorance.

We really know very little about exposure to these chemicals.

O'BRIEN: Beverly Paigen had done groundbreaking research about environmental hazards.

She had written papers suggesting that air quality might contribute to lung disease.

That smog might contribute to asthma.

GIBBS: I met Beverly Paigen through my brother-in-law, and he introduced her as a scientist, a health scientist, who could be helpful.

And she came by to the first meeting.

She goes, "I know everybody is really upset "about the chemical exposure, "and I don't know what that means yet, but I'd like to help you figure that out."

...to test for liver function.

There will be counts done on your blood cells... HAY: She approaches the residents in a very different manner than the Department of Health.

She had expertise, but she did not walk in as the authority.

Any other questions?

HAY: She listens to them.

She takes it as legitimate, their concerns that there are illnesses in that broader, expanded, outer ring area.

PAIGEN: There may be some problems that will not be solved by the cleanup.

Besides the first ring... LESTER: The Health Department constantly said, "If you're outside of the fence, you're not at risk."

But there was no basis for saying that.

There was no science for saying that.

And the fence became a symbol of who was safe and who was not.

The residents, of course, looked at that fence and said, "What are you talking about?

"These chemicals are in the air.

They're not being stopped by the chain link fence."

(camera shutter clicks) So it also became a battle line between what the community wanted and what the state was willing to do.

GIBBS (archival): There was a man on 102nd Street who just came back from Cleveland Clinic diagnosed an epileptic.

He's never had any central nervous system problems of any sort, and all of a sudden, you know, he's got this crazy seizure problem.

(in interview): We needed to try and find out what's going on in the outer community.

Was it our imagination, this cluster of epileptics?

Is it a coincidence that these women are having miscarriages, or is it real?

Because the soils are contaminated... (in interview): And so we just wanted to see what was really going on.

We wanted to find-- no one else would tell us, so we'll find out for ourselves.

And that's when we did the health study.

O'BRIEN: Lois Gibbs and the other mothers didn't know how to conduct health surveys.

Beverly Paigen gives them a way to do that.

She tells them what questions to ask, how to ask them.

And with her help, uh, they're able to start building their own data.

GIBBS: We were at my house one night, and we're, like, putting these things on a pin map, and it was, like, "Red is for miscarriages, blue is for cancer," whatever the color code was.

And we were realizing that, "Oh, my gosh, some of these things are really clustering."

Like, "Epilepsy around my house, um, and, you know, birth defects over here."

CURRY: One neighborhood was severe heart and lung problems, and another neighborhood was female cancers.

And then in my area, there was a lot of miscarriages.

GIBBS: So we went back and started interviewing people in those areas where there was clustering of diseases.

And the old-timers would tell us about an old creek that was there.

(slide shifts) And how it was backfilled with, um, construction waste and then dirt.

O'BRIEN: Sometime in 1978, the State Department of Health unearthed aerial photographs of the neighborhood just before Hooker Chemical began using the land as a dump.

And in these photographs, there was a series of streams, or, as they called them, swales, that cut through the neighborhood, moving in every which direction.

But when Lois began to connect the dots, finding these clusters around the old swales, and, and Beverly studied it for herself, she was alarmed.

PAIGEN: Well, this is actually quite interesting.

This stream here has very little disease along it, and this stream never intersected Love Canal.

There's no disease along here.

There are about 40 homes in here, and there's about seven or eight dots.

There are about 40 homes in here, and there's at least 50 dots.

These are just half-a-block away.

They're both on a stream, but one stream intersected Love Canal and one didn't.

This is some of the strongest evidence I have... O'BRIEN: If it was true that human health problems seemed to follow the old swales, then it was true that the human threat was much farther than state and federal officials had originally indicated.

Beverly Paigen ultimately flew to a meeting in Albany with these maps and with this data.

And she recalled that when she boarded the plane that day with this tube of, of maps and photographs, that she felt like she was carrying something explosive.

She said she felt like she was carrying a bomb.

PAIGEN: So I flew to New York State Health Department and proposed this as a hypothesis to them.

"Why don't you look at disease in these homes "which are along swales, "compared to the homes which are not, to see if there's a difference in disease incidence?"

And they agreed to do that.

What happened, though, was quite different.

I'll never forget it, because I got on the airplane, flew back to Buffalo, picked up a newspaper in the airport, and there was a story on the front page attacking my hypothesis.

O'BRIEN: The same health officials that she had met with in Albany had spoken to the press, and they dismissed what she had presented that day.

RICE (archival): The women told us the state office had dismissed their studies as "useless housewife data."

They thought we were useless housewives.

We're just dumb little housewives.

I never heard of anything so insulting.

The "useless housewife data"?

Yeah.

And there was hundreds and hundreds of hours put into that paperwork.

GIBBS (archival): I'm not a scientist.

I am a housewife, as I've seen quoted in the paper many times.

My data is not useless, it is not pointless, and it's not invalid.

Every one of these people in this audience plus gave me that data.

They don't lie.

What you're doing in the Health Department is going to take six months, eight months, ten months.

And if we sit and wait for six more months, we're going to have dead children.

♪ ♪ (in interview): Government talked down to us all the time.

"Where did you learn epidemiology?

You can't even say it."

But we weren't intimidated.

"It was fine-- do whatever you want.

But we're going to keep moving."

Cancer's not the only thing these chemicals cause.

GIBBS: But I think Beverly didn't feel the same way.

She was a professional, a researcher, and she worked for the New York State Health Department, so the ramifications for her actions was tremendous.

DAVID AXELROD: Dr. Paigen will readily admit that the procedures which she used for the gathering of data are not generally acceptable.

THOMSON: From the state's perspective, all the health study did was amass anecdotal data and map it onto one understanding of the neighborhood's environment, which is very complex.

You would need to know what chemical was there, how long it had been there, how that interacts with people's individual biological makeup, how much time they actually spend in their house, what do they get exposed to at work?

It is virtually impossible to establish causality.

O'BRIEN: And so for David Axelrod, for the E.P.A., for other officials in New York and Washington, it was very difficult to know where to draw the line.

Who was safe and who wasn't?

(machinery whirring) NEWMAN: Over and over again, what you see with Love Canal is that it was a first.

They're trying to clean up a hazardous waste site that sits below an occupied neighborhood.

How do you do that?

It's never been done before.

A lot of these chemicals have a very low igniting point.

So if your prober went down and it hit a barrel, that could cause an explosion, right?

I would say no, because we'll use the metal detection... (audience clamoring) ...ahead of anything else.

We will not be probing any area... All right... GIBBS (in interview): The work itself was totally terrifying.

Nobody knew what was going to happen.

If there was a spark from the backhoe hitting a barrel or something, the whole thing would blow up.

REPORTER: We're talking about the possibility of the entire dump exploding.

MAN: Well, not the entire dump, but there could be an explosion.

There, there may be, uh, exposures of gas or something like that.

Those are, are probably not going to happen, but you can't be sure they're not.

What are we going to do if this blows up?

REPORTER: Buses are standing by at a cost of $6,000 a day, just in case of an emergency evacuation.

PATTI GRENZY: So they put buses in the neighborhood, and they sat there with their engines going all day.

The idea was that if there was an emergency, those bus drivers that they hired would sit there and wait for you and your children to run down the street to, to get on a bus if there was an explosion.

REPORTER: Another precaution was taken for residents still living in the area.

They participated in a test bus evacuation from the area Monday, with 60 bus drivers involved in the simulated evacuation plan.

DISPATCHER (over radio): All Love Canal charter buses this frequency, upon arriving at the Love Canal site, please check in.

(talking in background) GIBBS (in interview): We had our papers and our knapsacks ready to grab and run.

This is like your mortgage, your health insurance, the stuff you put in a safe in case of a fire, right?

We're going to have to grab our baby, grab our knapsack, and it, it was insane.

We literally, every single day, had to wake up to the reality that we may have to run for our lives.

KENNY: I started reading all of these articles around the beginning of August.

I was aware of what was happening, that they had been evacuating the whole area.

And I'm just thinking, oh, it's a block and a half away and it really doesn't affect me.

I was working full time.

I would go in at 7:30 in the morning and come home and be able to pick the children up at school.

Steven was nine years old and Chris was 11, and Jon was six years old.

Jon was such a little imp.

He had this black curly hair, had the sweetest smile, and there was something special about him, something very special.

It's 45 years later now, but I still feel... You know, I still feel it.

June of 1978, Jon suddenly, his stomach was distended and he was swelling up, so it looked like he was getting allergies.

But the pediatrician took one look at him, and, and she knew exactly what was wrong with him, that he had immune response disease called minimal lesion nephrosis.

But they told me it was the best disease a child could have, because it's treatable, and, and he'd be over it by the time he's 14.

Most children with nephrosis do very well.

Um, they may have, uh, a relapse sometime shortly after the initial episode, but most of them go on to, to lead perfectly healthy lives with no further recurrences.

KENNY: Jon was in the hospital for a whole month.

The nurses loved him because he was not a difficult patient.

You know, he didn't complain.

Finally, with treatment, he went into remission and he was sent home again.

As soon as he would come home, within a few days, he was no longer in remission.

I would take him in the hospital, and he'd go into remission.

Then I'd take him back home again.

Then the remission was gone, and it was the same story.

So it was very strange.

Unfortunately, I didn't know, I mean, he was playing in the backyard, he was a little kid.

You know, his favorite pastime would be to play games in the back of the house.

We just didn't know what was in the backyard.

(news theme playing) REPORTER: Hooker Chemical landfills have been a cause for concern for quite some time in Niagara Falls.

For many, that concern has turned to outright fear, now that the deadly chemical dioxin has been discovered at Love Canal.

REPORTER 2: Dioxin is a by-product of a herbicide used widely by the U.S. Army to defoliate dense Vietnamese jungles.

BROWN: I knew, months before it was considered an emergency, that Hooker had manufactured components of dioxin, at least 200 tons of it.

That was as much dioxin as had been spread in Vietnam with all the Agent Orange.

That was the amount that you could calculate as being in the Love Canal.

PAIGEN: Well, dioxin is a very toxic chemical, most toxic chemical that's ever been made by man.

LESTER: Dioxin is a highly potent carcinogen.

And it causes its effects at the parts per trillion level, which is even hard to comprehend.

MAN: Now, 1/30th of an ounce of this dioxin will kill five million guinea pigs.

LAVERNE CAMPBELL: We are naturally concerned over finding dioxin, but it does not come as a surprise, nor does it cause us to make any further recommendations at this time.

The commissioner said there is no evidence to indicate that the trace amounts of dioxin found in the leachate pose an immediate health hazard to residents of the area.

MAN: How does it affect the kidneys, the heart, the eyes, or any vital organs?

Do you know this?

CAMPBELL: I don't know the answer.

Who does know in the Health Department of New York State?

There are a number, including Dr. Axelrod.

Now... Could, could this person be brought here to answer these questions?

He was here the other night.

I've got a book on it, toxicology book.

It'll tell you-- ultimate is death.

CAMPBELL: That's the answer.

Get it out of there.

KENNY: By the middle of September, Jon was so sick, he just spent the whole time laying on the couch.

When we took him to the hospital, his stomach was so distended, we had to put suspenders on him.

Soon he was in an oxygen tent, couldn't breathe, and he looked scared.

He had those big, brown eyes that were staring out at us through there.

And we tried to reassure him, and tell him he'd be okay, and that we were going to be nearby, that... You know, 'cause they wouldn't let us stay, you know?

(people talking in background) My mother had packed some eggplant Parmesan sandwiches.

We went to the cafeteria to eat, and all of a sudden, we hear his doctor being paged to the I.C.U.

(woman speaking on intercom) Norman and I ran out of that room.

We threw the sandwiches in the garbage.

And we went there, and, and, um, I mean, we knew.

We just knew.

The first thing I blurted out was, "I want an autopsy," because they told me that it was the best disease that a child could have.

You just can't believe it, that he was gone, like that.

People said, "Well, yes, Mrs. Kenny, probably your son's death was due to the chemicals."

I kept saying, I said, "I don't think so."

I said, "I, I want to see the evidence first."

Maybe it's the scientist in me.

My husband was also a scientist, so we were trying to be objective, I mean, I'm not going to jump on a bandwagon when I have no proof.

My husband and I went to the medical libraries, and we started researching.

I found all of these articles that said that nephrosis could be caused by exposure to chemicals.

♪ ♪ It was one of the worst feelings I've ever had, because I did not want it to be that.

You just wonder, I mean, how did you miss it, you, you know?

But you did.

♪ ♪ Later on, they come out and they say there's dioxin behind where my house was.

There's 32 parts per billion in that creek.

I mean, Jon was back there all the time.

♪ ♪ You know, you blame yourself-- "Why didn't we move?

Why did you do this?

Why didn't you do that?"

I mean, "You should have been paying attention."

(dog barking in distance) PATTI GRENZY: When Luella lost her son, once you get past feeling so horrible for them, then, somewhere in the back of your mind, that little voice is saying, "That could be you.

That could be your kids."

(machinery running) CURRY: They found it in my backyard, too.

They found dioxin on the surface soil, where my kids crawled on their hands and knees and chewed on the toys and all.

(slide shifts) So it was getting scarier and scarier.

REPORTER: The residents want the cleanup operations at the Love Canal to stop, they want families to be evacuated because of high amounts of the toxic chemical dioxin that has been found.

GRANT-FREENEY: We felt that yes, the cleanup was dangerous, and that the people doing it really didn't know what they were doing.

It was more like an experiment.

(machinery running) If you're disturbing chemicals, then you're releasing them into the air.

We were already having problems with them, but to open them up, we didn't know if people were going to be dropping dead or what, but... (chuckles) Sometime I sit back and I says, "Did I live through that?"

CURRY: We had the trucks driving through the neighborhood with dirty tires after they had driven on the canal itself.

And, and then people would walk down the road, and they'd go in their homes, and, and it was just a mess.

So we knew that digging was making things worse in the neighborhood.

We had to raise holy hell to stop that.

Picket signs are up tonight in the Love Canal area of Niagara Falls, New York, as angry residents try to stop excavation work.

REPORTER: It was not a warm welcome for construction workers at the Love Canal this morning.

They were greeted by angry canal residents walking a picket line at each gate leading into the area.

GIBBS: We protested literally every day.

Mostly us at either end of the canal, not letting the trucks come in.

REPORTER: In addition to yelling, picketers also lectured every worker on the hazards of dioxin, a dangerous chemical which was discovered... GIBBS: We never were able to actually stop them, but it was more to educate our local leaders and our local community, but also the media, to say, "Look at, this is what's happening."

REPORTER: Eight more arrests today at the Love Canal area of Niagara Falls, New York.

OFFICER: Take a seat in the car, please.

O'BRIEN: Initially, politicians weren't afraid of Lois Gibbs or any other mother.

But within a couple of months, they were.

Especially Governor Hugh Carey.

He was up for reelection.

He was in a dogfight to win.

(talking softly) O'BRIEN: Governor Carey made multiple visits to the Niagara Falls area.

He made sure he was photographed with Lois Gibbs.

(camera shutter clicks) GIBBS: I was a political threat to him.

I could unseat him.

(shutter clicks) The same was true with President Carter.

(shutter clicking) I was their enemy.

I was their worst nightmare.

We decided that Governor Carey was the one who could give us what we wanted, and so we just targeted him.

(people yelling indistinctly) Every time he came to anywhere in Western New York, there was a troupe of people who would go and greet him.

Well, my seven-year-old son is already dead, Governor Carey.

Now, you're not attributing the death to what happened...

Yes, I am.

All right.

And I have plenty of evidence for it.

Let me put it this way.

You're aware this state has spent $23 million to help the residents of Love Canal.

If there's any way that...

I'm aware they've spent it and they've avoided me for seven months.

WOMAN: We don't want you to just clean it up first.

We want to be moved out first before you clean it up.

All right.

WOMAN 2: You want to tell these kids that get sick all the time?

We've moved all, we've-- I think the children might well be exposed, in danger by being brought out here and walking around in the rain this way.

(all talking at once) KENNY (in interview): And he's looking at us, saying, "Well, if you're so concerned about your children, why don't you take them home?"

You know, "Don't stand here out in the rain."

You know, after a while, you can just take so much.

Within, within a... Do I have to lose another child?

Within a day, we'll know whether the evaluation... Now, please, I'm not the one who's causing the death of children around here.

I'm the governor who came... WOMAN: Yes, you are, because you have the power to relocate us.

We relocated everyone who was affected by the... We are being affected!

RICE: Those women kept that story out there, and they quickly learn, especially for us, the television media, we can't tell a story without pictures.

So they would come up with all different ways to get our attention, which would get the cameras there.

(camera shutter clicking) REPORTER: Reacting to White House refusal to buy their homes, angry residents of chemically polluted Love Canal dragged out dummies in the street and burned the Carter family in effigy.

(people cheering) (chanting): We want FEMA!

We want FEMA!

PATTI GRENZY: My mother used to say, "They're just using you," meaning the, the media.

I said, "Yeah, Ma, but we're using them."

We kept them busy with stories, so they kind of, like, scratched our back and we scratched their back.

ERNIE GRENZY: On Saturdays, I could go and I could protest, and we brought our kids, and we would be yelling, "We want out, we want out."

And I remember being home one day, and, and my girls were three and two, or less, and I hear from the bathroom, they're in the tub, they're yelling, "We want out, we want out."

It was funny at first, but then after it settled in, you're wondering, you know, really, how does it affect them?

'Cause we don't know.

REPORTER: The boarded-up houses are the visible evidence of fear, but the experts say that the problems here go far beyond what you can see.

Love Canal has been called a mental health disaster.

WOMAN: My marriage is broken up right now.

I, I have no other... CURRY: Just our block alone, I, I was flabbergasted to see how many people divorced.

(camera shutter clicking) People were riled up and angry, and there was no place to take that anger to, so then the wives and the husbands were fighting.

(shutter clicking) My husband couldn't understand why I had to keep going.

I tried to explain to him that, "These people helped you get out, "and if it wasn't for those people, we'd be still stuck in Love Canal."

I had two fights going on.

It was, was not a good time.

(archival): What do you suppose you're going to do about moving costs?

And I don't care where they're from in this area.

These people can't afford to move out and come up with this front money.

It's just not there.

I said I didn't have any easy answers for you.

We've just come up today, and we've begun to work with the State of New York.

ERNIE GRENZY: The state held most of their meetings and their press releases and all that stuff while I was at work, and left the wives to fight.

And the state made a big mistake by doing that, because the women fought more than any man could.

Hell hath no fury like a woman guarding her children.