Industrial Expansion West and Its Impact

Clip: Episode 1 | 8m 52sVideo has Closed Captions

After the Civil War, Americans set out with renewed energy to unite the East and West.

After the Civil War, Americans set out with renewed energy to unite the East and West. They built railroads to span the continent, opening up vast areas for homesteaders and connecting distant metropolitan markets to domestic crops and cattle. The effect on the environment, the bison, and the Plains Indians was catastrophic.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding for The American Buffalo was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and its...

Industrial Expansion West and Its Impact

Clip: Episode 1 | 8m 52sVideo has Closed Captions

After the Civil War, Americans set out with renewed energy to unite the East and West. They built railroads to span the continent, opening up vast areas for homesteaders and connecting distant metropolitan markets to domestic crops and cattle. The effect on the environment, the bison, and the Plains Indians was catastrophic.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The American Buffalo

The American Buffalo is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

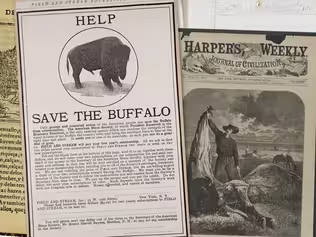

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipBy the end of the 1850s, the bison had been driven from all but the interior portion of the Plains, where, by the mid-1860s, an estimated 12 million to 15 million of them still lived.

West: That's a lot of bison, 12 million to 15 million animals.

There were still a lot of bison to hunt.

And there would remain to be a lot of bison there up until into the 1870s, when the real hammer fell.

Man: "We saw the first train of cars that any of us had seen.

"We looked at it from a high ridge.

"Far off it was very small, "but it kept coming and growing larger all the time, "puffing out smoke and steam.

"As it came on, we said to each other that it looked like a white man's pipe when he was smoking."

Porcupine.

[Train whistle blowing] Narrator: After the Civil War, Americans set out with renewed energy to unite the East and West, building railroads to span the continent, opening up vast areas beyond the Missouri River for homesteaders, creating easier access to distant metropolitan markets for crops and cattle, and servicing the demands of boom towns that had sprung up after gold discoveries in the mountains of Colorado and Montana.

Man: There are lots of technologies that move into the Great Plains in the 19th Century, and most of them have a negative impact on the bison.

But all of this pales in comparison to a sort of spasm of industrial expansion into the Great Plains after the Civil War.

Narrator: Native people called this newest arrival "the Iron Horse," and the pace of change quickened as never before.

As the Union Pacific pushed west across Nebraska toward California, the Kansas Pacific aimed for Denver, piercing into the heart of the buffalo range of the Central Plains.

To feed the hungry crews laying track, the railroad company hired an ambitious and flamboyant 21-year-old Union veteran, paying him $500 a month to keep them supplied with the meat from twelve buffalo a day.

His name was William F. Cody.

Within a few years, he would be known by a different name.

Man as William F. Cody: During my engagement as a hunter for the Kansas Pacific, I killed 4,280 buffalo.

It was not long before I acquired a considerable reputation and the very appropriate name of "Buffalo Bill" was conferred upon me by the railroad hands.

It has stuck with me ever since, and I have never been ashamed of it.

[Horse neighing] Narrator: To publicize its progress across the Plains, the Kansas Pacific promoted excursion trips for passengers eager to have the chance to see-- and shoot at--the buffalo they were sure to encounter.

A church group from Lawrence, Kansas, organized a two-day outing to raise money for the congregation.

300 people signed up.

On the second day, they came upon a herd.

[Gunshots] Man: "The buffalo kept pace with the train "for at least 1/4 of a mile, "while the boys blazed away at them without effect.

"Shots enough were fired to rout a regiment of men.

"The train stopped, and such a scrambling and screeching "was never before heard on the Plains, as we rushed forth "to see our first game lying in his gore.

"I had the pleasure of first putting hands "on the dark locks of the noble monster "who had fallen so bravely.

"Then came the ladies; a ring was formed; "the cornet band gathered around and played 'Yankee Doodle.'

"I thought that 'Hail to the Chief' would have done more honor to the departed."

Woman: "When the white men wanted to build railroads "or when they wanted to farm or raise cattle, "the buffalo protected the Kiowas.

"They tore up the railroad tracks and the gardens.

"They chased the cattle off the ranges.

"The buffalo loved their people as much as the Kiowas loved them."

Old Lady Horse.

Narrator: For decades, Native tribes had resisted incursions onto their homelands, and the army had built forts in response.

Now more forts were established and more troops were dispatched to man them.

Indian warriors attacked survey crews and road gangs, sometimes even derailed trains.

The army's retaliations were ineffective, and, in 1867, Congress decided to try a different approach.

Delegations were dispatched to pursue what some called "the hitherto untried policy of conquering with kindness."

That October, more than 5,000 Kiowas, Comanches, Arapahoes, and Southern Cheyennes gathered at Medicine Lodge Creek in Kansas to hear a proposal from U.S. officials intended to end the violence on the Southern Plains.

Under the government's plan, the United States would encourage white settlement north of the Arkansas River.

The Indians would move onto reservations in what is now Oklahoma, where they could receive food and supplies for 30 years, be provided schools for their children, and taught how to farm.

The Kiowa chief Satanta objected.

Man as Satanta: I want you to understand what I say.

Write it on paper.

I don't want to settle.

I love to roam over the prairies.

There I feel free and happy, but when we settle down, we grow pale and die.

Narrator: "Do not ask us to give up the buffalo for the sheep," Ten Bears of the Comanche added.

"Do not speak of it more."

The peace commissioners promised that, south of the Arkansas, non-Indians would be prohibited from settlement, and the tribes could continue hunting there "so long," the treaty said, "as the buffalo may range there in such numbers as justify the chase."

Though not every band of each tribe was represented, the treaty was signed and sent to Congress.

The Kiowa calendar for that year showed an Indian and a white man shaking hands near a grove of trees.

West: The government comes away from that treaty thinking that it has set in motion this transformation of Indian peoples from hunting, gathering, semi-nomadic people to farmers.

The Comanches and Kiowas come away from that treaty thinking that they have now permission to continue doing what they have always done, and therefore achieving absolutely nothing.

Narrator: A year later, farther north, at Fort Laramie on the Platte, a similar treaty was signed by some of the Lakota Sioux.

In exchange for the government abandoning its Army forts in Wyoming's Powder River country, a vast Sioux reservation was created, encompassing half of present-day South Dakota, including the sacred Black Hills.

The treaty also contained a clause stating the Lakotas were free to hunt outside the reservation, so long as there were buffalo.

General William Tecumseh Sherman, now in command of the army in the West, reluctantly agreed to the hunting concession.

"This may lead to collisions," Sherman wrote his brother, "but it will not be long before all the buffaloes are extinct near and between the railroads."

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep1 | 10m 24s | The U.S. government made treaties with Indigenous people when it was convenient. (10m 24s)

Surprising Facts About the Buffalo

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep1 | 9m 40s | Did you know a buffalo can clear a six-foot fence? (9m 40s)

Why Is Destruction Part of Our Story?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: Ep1 | 9m 59s | The scale of wild animal loss during the 1800s is the largest in known human history. (9m 59s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Corporate funding for The American Buffalo was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and its...